Historical Sites on ADV Bikes: Mt Lemmon Prison Camp

Tired of riding the same routes each month? Get out and explore Arizona's rich history with our series of Historical Sites for ADV Bikes!

Getting to Mount Lemmon Prison Camp we'd rate at a 1 out of 5 difficulty rating if you only take the highway up and down. With 26 miles of curves each way; it's the perfect summer ride in Southern Arizona because of the massive drop in temperature towards the top. The prison camp is at mile marker 7 as you ascend the highway and is a great place to camp if your planning an overnighter. Weekends get busy on the mountain, as you might expect, and slower moving traffic doesn't seem to recognize what the multiple pull-outs along the highway were designed for most of the time. For maximum enjoyment, we recommend riding Mt Lemmon on weekdays.

To make this ride dirty, ride the offroad section on the backside of Mt Lemmon from Oracle! Maps call it the Arizona National Scenic Trail. Difficulty peaks at a 3.5 out of 5 and we recommend you be an intermediate rider or better if you're attempting it on a big ADV bike. Most of the way up the mountain it's an easy, well groomed, road but as you start climbing in elevation the road turns rocky and loose in sections. Riding this road up or down the mountain is spectacular but this road does close for the winter months so check with locals for when the gates open/close. May to October it's usually open.

Enjoy the history:

In the rugged Santa Catalina Mountains overlooking Tucson, Arizona, the winding Catalina Highway leads travelers through a dramatic transition of ecosystems—from saguaro-studded deserts to pine-scented forests. Thousands of people drive this road every week to reach the cool summit of Mount Lemmon, but few realize that the asphalt beneath their tires was laid by men who were imprisoned for their conscience.

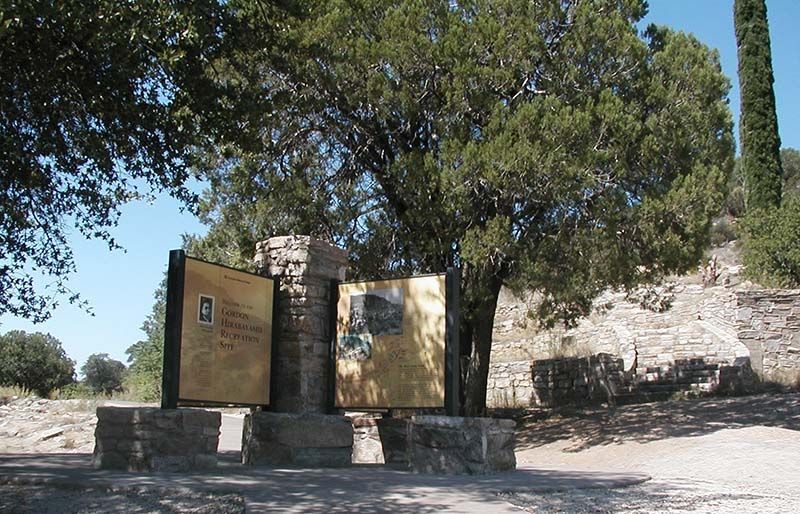

At Mile Post 7, a quiet campground and trailhead now bears the name of one of these men: Gordon Hirabayashi. The site of the former Catalina Federal Honor Camp serves as a solemn reminder of a time when wartime hysteria eclipsed constitutional rights, and one man’s "stupid honesty" became a beacon for American civil liberties.

The Man Who Said "No"

Born in Seattle in 1918 to Japanese immigrant parents, Gordon Hirabayashi was a senior at the University of Washington when the world fell apart. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. government issued Executive Order 9066, which eventually led to the forced removal and incarceration of over 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry—two-thirds of whom were American citizens.

Hirabayashi was a religious pacifist and a member of the Quaker-inspired Mukyokai movement. When the military imposed a curfew specifically for Japanese Americans and later ordered them to report to "relocation centers," Hirabayashi felt a fundamental conflict. "If I were to maintain my integrity in terms of my belief that I am a first-class American citizen," he later wrote, "but then accepted second-class status, I would have had to accept all kinds of differences."

He refused to obey the curfew and refused to report for internment. Instead, he walked into the FBI office in Seattle and turned himself in. He wanted a "test case" to prove that the government could not legally imprison citizens without due process based solely on their race.

The Long Road to Tucson

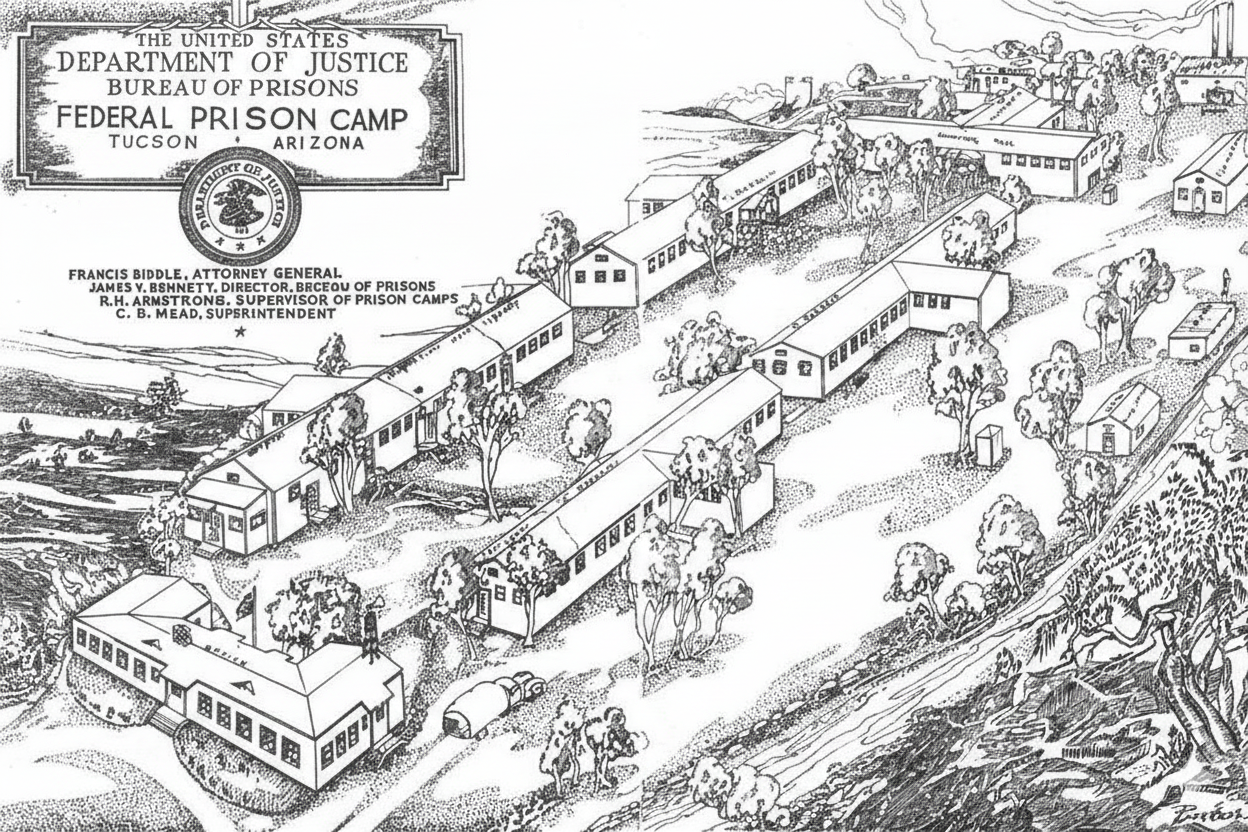

Hirabayashi’s legal battle went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a landmark (and today, widely criticized) 1943 decision, Hirabayashi v. United States, the court unanimously upheld his conviction, ruling that the curfew was a "military necessity." Hirabayashi was sentenced to 90 days in prison. However, because he was in Washington state and the nearest "honor camp" with space was in Arizona, a logistical problem arose: the government didn't want to pay for his train fare. In a display of character that seems almost unfathomable today, Hirabayashi offered to get himself to prison. He spent several weeks hitchhiking 1,600 miles from Spokane to Tucson. When he finally arrived at the gates of the Catalina Federal Honor Camp on Mount Lemmon, the guards couldn't find his paperwork. They told him to "go into town, catch a movie, and come back later." He did exactly that, returning to the camp once his papers were found to begin his sentence. The camp where Hirabayashi served his time was not a typical prison. Established in 1937, it was a "prison without bars," designed to house low-security inmates who provided the back-breaking labor required to build the General Hitchcock Highway (now Catalina Highway).

Life on the Mountain

Inmates lived in wooden barracks at about 5,000 feet of elevation. Their days were spent:

- Blasting Rock: Using dynamite to carve through the granite of the Santa Catalinas.

- Manual Labor: Clearing brush, moving heavy stones with sledgehammers, and operating jackhammers.

- Survival: Facing Tucson’s extreme temperature swings—from scorching summer afternoons to freezing winter nights.

The "Tucsonans"

During World War II, the camp’s population shifted. Alongside traditional inmates were "resisters of conscience." This group included:

- Japanese American Resisters: Men like Hirabayashi and a group known as the "Tucsonians" who protested the loyalty oaths and internment.

- Jehovah’s Witnesses and Quakers: Conscientious objectors who refused to serve in the military on religious grounds.

- Hopi Indians: Tribal members who refused to register for the draft, citing their own sovereign status and religious beliefs.

These men formed a unique community of intellectuals and believers, often spending their evenings discussing philosophy and the Constitution while the mountain wind whistled through the barracks.

Vindicated by History

After serving his time in Arizona (and later another year in federal prison for refusing the draft), Hirabayashi went on to have a distinguished career as a professor of sociology. However, the shadow of his criminal record remained for four decades. The turning point came in the 1980s. Legal researcher Peter Irons discovered evidence that the government had suppressed its own intelligence reports during WWII—reports that stated Japanese Americans posed no actual threat. This "prosecutorial misconduct" allowed Hirabayashi to reopen his case. In 1987, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated his convictions. The court noted that "the government’s position was based on racial prejudice and wartime hysteria rather than military necessity."

The Ultimate Honor

In 1999, the site of the old prison camp was officially renamed the Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site. Hirabayashi himself attended the dedication ceremony. In 2012, shortly after his death, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States.

Visiting the Site Today

If you visit the Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site today, you won't find many buildings. Most were razed in the 1970s. However, the spirit of the place is palpable. You can still walk among the concrete foundations of the mess hall and barracks. Detailed panels tell the story of the camp, the construction of the highway, and the struggle for civil rights. Standing at the site, you can look up at the towering cliffs and down toward the Tucson valley, reflecting on the fact that the road you traveled was built by men who were held here for simply believing in the promises of the Constitution.

The Legacy of "Stupid Honesty"

Gordon Hirabayashi’s father was often teased by his peers for being baka shojiki—meaning "stupidly honest." He didn't hide the best lettuce at the top of the crate; he was exactly who he said he was. Gordon inherited this trait. He could have easily "gone along to get along," but his refusal to compromise his identity as a "first-class citizen" eventually forced a nation to confront its own failures.

The next time you drive the Mount Lemmon highway, take a moment to stop at Mile 7. Listen to the wind through the oaks and remember that sometimes, the most important roads we travel aren't made of asphalt, but of the courage to stand still when everyone else is being forced to move.