Historical Sites on ADV Bikes: Sunnyside

Tired of riding the same routes each month? Get out and explore Arizona's rich history with our series of Historical Sites for ADV Bikes!

Getting to Sunnyside we'd rate at a 2 out of 5 difficulty rating. It's a great offroad section that easy enough for beginners with one mild technical dry creek crossing. The road is big bike friendly. If you continue past Sunnyside, you'll run into slightly more technical terrain, but again, nothing we'd consider difficult, even on the largest ADV bikes. Enjoy the history:

In the rugged, pine-scented folds of the Huachuca Mountains in Cochise County, Arizona, lies a history that reads more like a screenplay than a municipal record. Long before the suburbs of Tucson adopted the name "Sunnyside," a different community by that name thrived in a remote canyon, born from the spiritual fervor of a reformed sailor and sustained by the "common purse" of a communal mining experiment.

The story of Sunnyside, Cochise County, is a tale of religious zeal, copper dreams, and a specific brand of frontier socialism that existed nowhere else in the Wild West.

The Founding: Samuel Donnelly’s Revelation

The origin of Sunnyside is inseparable from its founder, Samuel Donnelly. Born in Scotland in 1852, Donnelly was a man of extremes. He spent his youth as a merchant seaman, allegedly living a life of "worldly" vices before a transformative experience at a Salvation Army meeting in San Francisco. Donnelly became a "two-fisted preacher," a charismatic figure who believed that the corruptions of the city were the greatest threat to a Christian life. In the mid-1880s, looking for a place to establish a utopian community, Donnelly turned his eyes toward the newly opened territories of Arizona. He wasn't just looking for a pulpit; he was looking for a livelihood. Donnelly acquired an interest in a mining claim on the western slopes of the Huachuca Mountains. By 1888, he had led a small band of followers—later dubbed the "Donnellites" by outsiders—into Sunnyside Canyon to build a town where work was worship and wealth was shared.

Operation: The Donnellites and the Communal Mine

Unlike the lawless mining camps of nearby Tombstone or Bisbee, Sunnyside was a model of sobriety and order. The town’s operation was built on three core pillars: mining, communalism, and strict moral discipline.

- The Copper Glance Mine: The economic heart of Sunnyside was the Copper Glance Mine. While many residents also worked at the nearby Lone Star Mine, the Copper Glance was the community’s project. Every man in the camp worked the mines or the sawmill. There were no private accounts. The profits from the ore were placed into a "common purse" used to provide for everyone’s needs, regardless of their specific job or status.

- Social Life in the Canyon: At its peak, Sunnyside housed between 80 and 100 residents. Life was simple but surprisingly rich in culture.Most meals were eaten together in a large tent or timber-framed dining hall. This fostered a sense of kinship that was rare in the highly individualistic West. Donnelly forbade saloons, gambling halls, and "camp followers" (prostitutes). To those living in the violent shadow of the O.K. Corral era, Sunnyside was a peaceful anomaly. Despite the remote location, the community valued refinement. Families owned instruments—including at least one rosewood piano hauled up the mountain—and children attended a one-room schoolhouse that doubled as a chapel.

- Religious Structure: The Donnellites practiced a form of "Primitive Christianity." There was no formal church building; instead, the canyon itself was the sanctuary. Donnelly preached daily, emphasizing that the physical labor of clearing rock and timber was a spiritual duty.

The Collapse: Floods and Failing Health

The fragility of a utopian community often lies in its dependence on a single leader or a single resource. Sunnyside had both vulnerabilities.

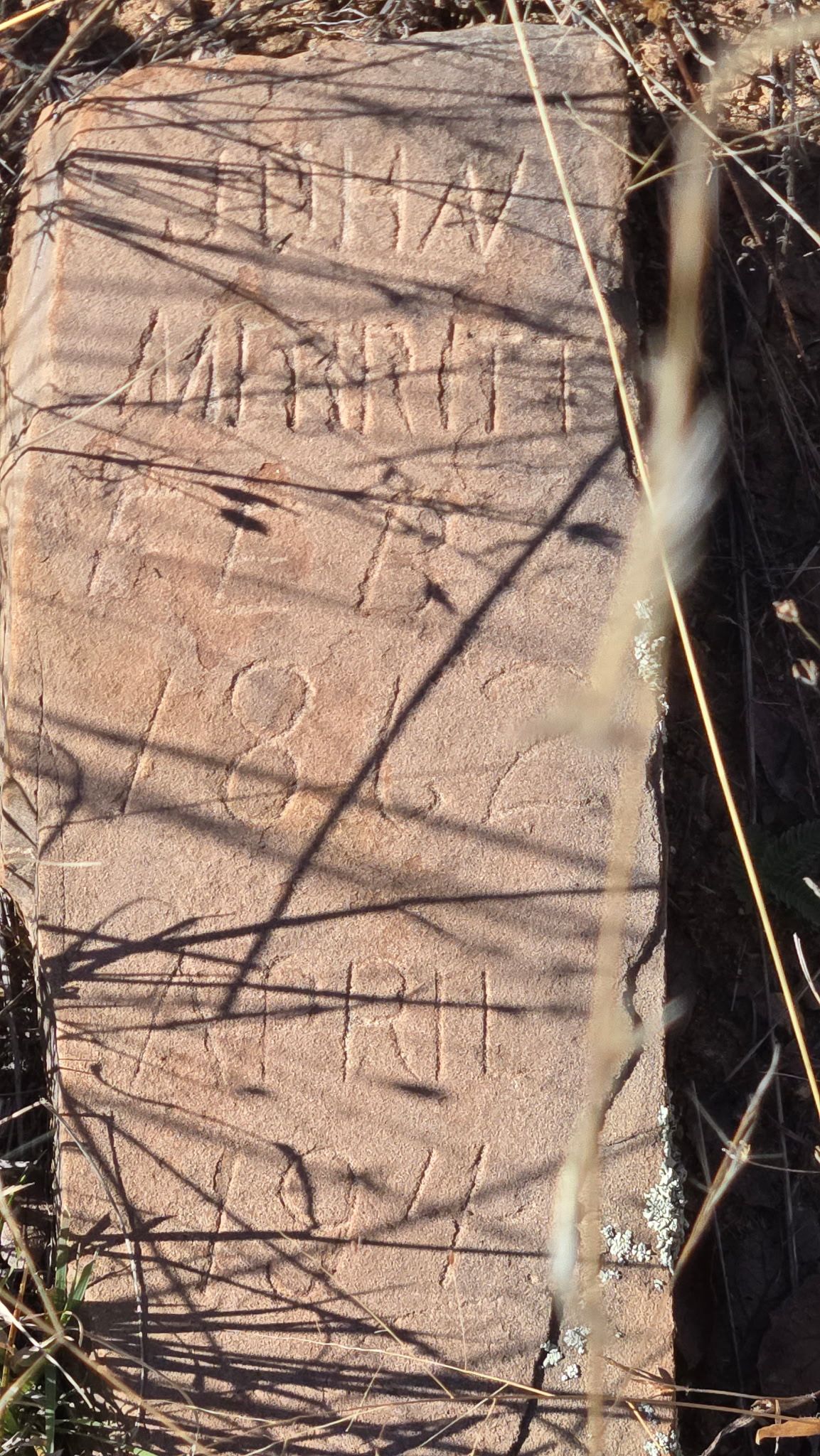

In 1898, a catastrophe struck the Copper Glance. Miners accidentally breached an underground aquifer, causing a massive influx of water that flooded the shafts. In an era before high-powered electric pumps, the mine became a watery tomb for the community's primary source of income. Without the "common purse" to sustain them, the Donnellites began to drift away. The final blow came in April 1901, when Samuel Donnelly died of Bright’s disease. Without his charismatic leadership to hold the commune together, the religious experiment effectively ended. By 1903, the town was nearly a ghost town.

The Second Life: Ranching and the CCC

Sunnyside didn't disappear immediately. In the 1910s and 20s, the area saw a small revival as a ranching community. A post office was established in 1914 and operated until 1934, serving the rugged homesteaders of the San Rafael Valley. During the Great Depression, the area's operation shifted again. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) established a camp nearby in 1933. These young men built the roads and fire lookouts that still exist in the Huachucas today, living in the same canyon where the Donnellites had once sung hymns.

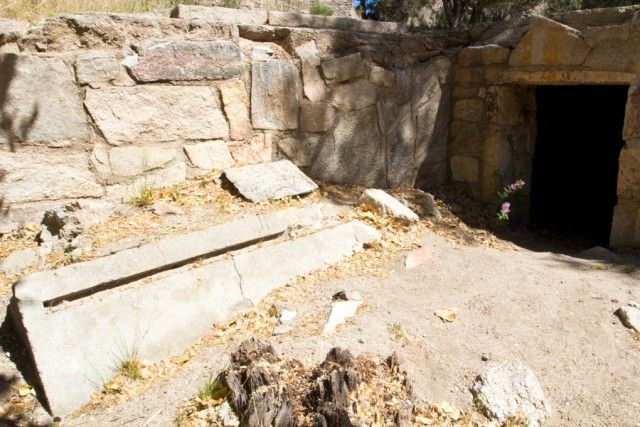

Sunnyside Today: A Modern Ghost Town

Today, Sunnyside is located within the Coronado National Forest. While most of the timber structures have rotted away, the stone foundations and the ruins of the "Hot House" remain as silent witnesses to Donnelly’s dream.The town remains a destination for hikers and history buffs, particularly those trekking the Arizona Trail, which passes near the site. It stands as a reminder that the history of Cochise County is more than just gunfights and outlaws—it was also a laboratory for those trying to build a better world in the middle of the desert.